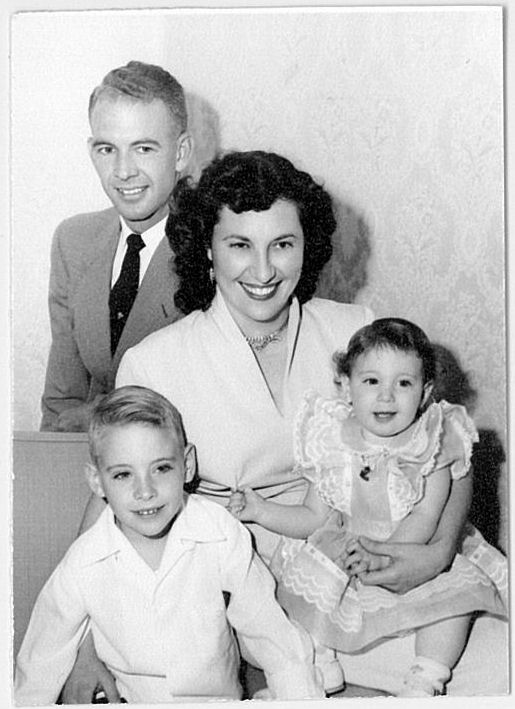

Max McDaniel, 77, Chevron Phillips Chemical’s longest serving research chemist and 2024 recipient of the Perkin Medal, was living in the Sahara Desert, North Africa, when he developed his life-long passion for chemistry, especially catalysts. McDaniel delivered these remarks at a Sept. 9 ceremony in Philadelphia honoring his achievements.

I think my career could be summed up as a love affair with the element chromium. This happened by chance because of several unplanned coincidences coming together during my life, which I will try to explain.

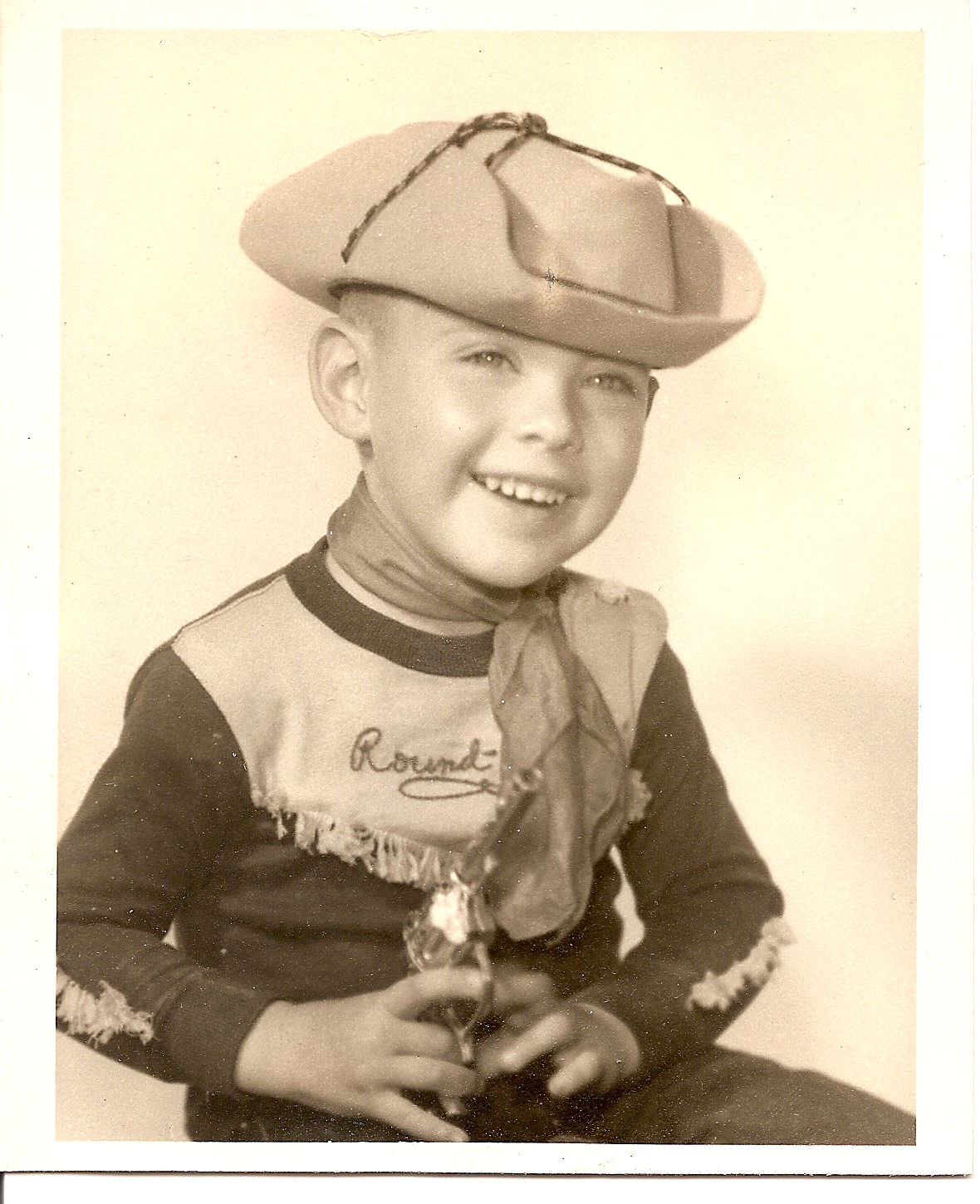

To start with, I grew up in the Sahara Desert. The people there were mainly Berbers, some Italians, and a few British and American petroleum exploration engineers and their families. I had a couple of good friends there, an American and an Italian. Compared to today, there were no organized programs for kids, no internet, no TV, no sports or parks. We spent most of our time either snorkeling along the Barbary Coast, where we found Roman coins and Barbary pirate cannon balls. Or we practiced a lot with a sling, as in the David and Goliath story. And after we had slung about a million rocks, we got to be pretty good at it, too. Even King David himself might have been impressed.

But mostly we were fascinated by the early space program. This was in the early 1960s after the Soviets had launched Sputnik and the U.S. had fallen behind in the space race. My father was a rescue pilot who was on standby when the capsules came down in the Atlantic. I read everything we could find out about each mission. I knew all the different rocket models and their statistics. And in imitation, my friends and I tried to make our own rockets too. And this is what started me out in chemistry.

I learned that for a few piasters, we could order potassium chlorate or nitrate from a local Italian pharmacy. Our chemical knowledge was very crude back then, because we had nothing to read. So, most of what we knew was learned through experimentation, just trial and error, which I think turned out to be good early training.

We would mix these two oxidants with various fuels found around the home, like sugar, or flour, or even tar from the roadbed, and cast them into metal casings, which became our rocket motors. Being in the Saraha, we had all the space we wanted, and nothing was going to catch fire out there, so our parents mostly left us alone.

Most of our rockets fizzled, some exploded, but occasionally – just occasionally --one would actually fly. And when that happened it was so exciting to watch something fly that we had figured it out on our own and built it with our own hands. Of course, they never flew in any predictable direction, but that didn’t really matter. And I was to learn later that that same feeling of intense satisfaction and exhilaration comes with discovery and creation in most any field of research.

Then one year the Libyans held a trade fair in nearby Tripoli. The western European countries set up exhibits showing off their most modern consumer goods, like household refrigerators and washing machines. And predictably, the Russians showed up with their heavy tractors and big industrial equipment. And in their exhibition was also a gorgeous collection of about two dozen chemicals. They were beautiful 8L glass bulbs with ground glass bottoms, just beautiful. In addition to fertilizers, the Russians also chose to display the most brightly colored industrial chemicals, one of which was the orange potassium dichromate.

Then one year the Libyans held a trade fair in nearby Tripoli. The western European countries set up exhibits showing off their most modern consumer goods, like household refrigerators and washing machines. And predictably, the Russians showed up with their heavy tractors and big industrial equipment. And in their exhibition was also a gorgeous collection of about two dozen chemicals. They were beautiful 8L glass bulbs with ground glass bottoms, just beautiful. In addition to fertilizers, the Russians also chose to display the most brightly colored industrial chemicals, one of which was the orange potassium dichromate.

My friends and I drooled longingly over those chemicals, so much so that after the fair closed about a month later, I went back to the fairgrounds and sought out the Russian manager of the exhibit. And I begged him to give me those chemicals. In retrospect, that took a lot of gall, because this was during the height of the Cold War, during the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis, and I was just a kid, and the son of an American military officer, too. But, to my astonishment, he agreed to give all of those beautiful chemicals to us. That was better than any Christmas I ever had!

Over the next few months, we conducted every kind of experiment with those chemicals that we could think of. Most of them, in retrospect, were totally stupid. And we particularly tested them in our rocket mixtures. After much trial and error, I discovered that adding just a small amount, a few percent, of potassium dichromate to our best propellent, would increase their burn rate by an order of magnitude. Very impressive.

That change made our rockets much more energetic. I don’t know if that impressive chemical reaction has ever been published anywhere in the scientific literature – and I doubt it -- but we discovered it on our own as kids. That was my first experience with chromium, and it was also my first experience with catalysis.

Later, when I went back to the States and entered college, I majored in (of course) chemistry. My undergraduate professor sent me to Northwestern in Chicago for a Ph.D., and there, by chance again, I worked on chromia catalysts. Then after coming to Phillips, I again worked on chromium catalysts under Paul Hogan.

I have had a very fortunate and interesting, and rewarding career working on chromium catalysts. I started out discovering chromium catalysis as a dumb kid, and now 65 years later, I’m still exploring it. And I’m still finding it just as fascinating and surprising as I did way back then. My son, Neal, is also a research chemist, working for Phillips 66, and he has the same strong feelings about his research that I do.

Our jobs have given us a chance to meet and learn from excellent scientists and engineers from all over the world, to build something lasting, and to participate in further exploration of some small, but still unexplored, part of the wider universe.